A closer look at the offence of Obstruction of Justice in Singapore (Section 204A Penal Code)

In an interview with CNA, Chooi Jing Yen shared his views on the offence of Obstructing Justice in Singapore, found in Section 204A of the Penal Code. He also shared how the law may affect tip-offs about police raids and traffic offences.

1. The Offence of Obstruction of Justice in Singapore

Section 204A of the Penal Code (Chapter 224, 2008 Rev Ed) criminalises the act of obstructing, preventing, perverting or defeating course of justice.

Anyone who is convicted of an offence under Section 204A may be sentenced to a fine and/or up to 7 years’ imprisonment.

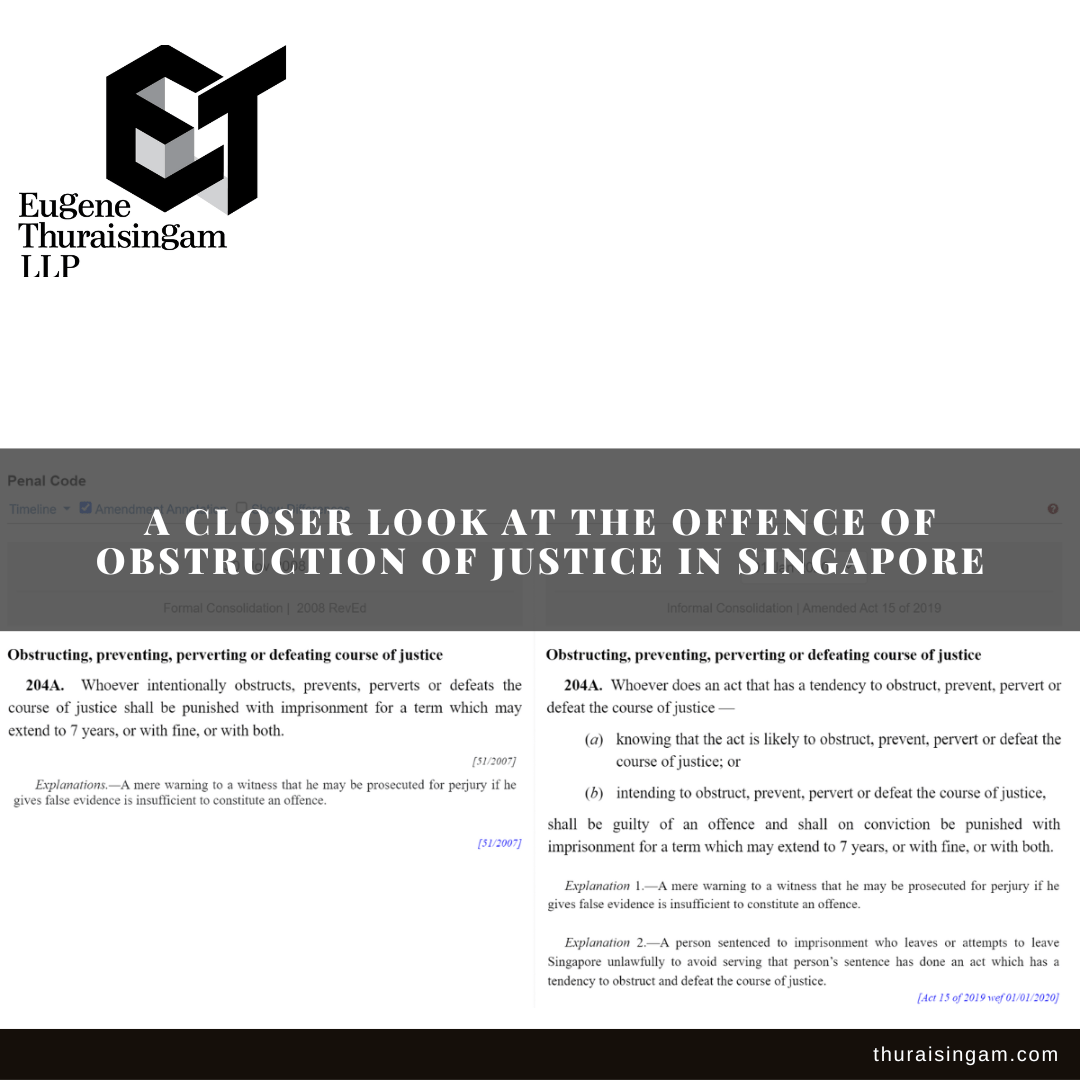

During the 2019 amendments to the Penal Code, Section 204A was substantially amended, and the current iteration of the provision came into effect on 1 January 2020.

2. Amendments to Section 204A of the Penal Code

Prior to the amendment of the Penal Code, Chooi noted that, to secure a conviction on a charge of obstruction of justice, the Prosecution needed to prove beyond a reasonable doubt that the offender possessed an intention to obstruct, prevent, pervert or defeat the course of justice.

In law, an intention is a higher threshold then, for example, recklessness or mere knowledge. This important distinction will become clearer when we compare the wording of Section 204A of the Penal code before and after it was amended.

For easy reference, we attach a screenshot of Section 204A of the Penal Code both before and after the 2019 amendments.

Thus, after the amendments, it may be easier for an offence under Section 204A to be established as the new provision is wider.

Whilst previously what was required was an intention to obstruct justice, the law post-Jan 2020 only requires that an offender does an act that has a tendency to obstruct justice whilst knowing that it is likely to obstruct justice. The mental element of the offence, which is referred to as the mens rea requirement in law, has been lowered by the amendments.

In Chooi’s view, on a plain reading of the law as it stands, this would capture a very wide range of conduct. One who informs another about police raids or, for example, the presence of a traffic marshall “need not know that a crime has been committed, nor that an enforcement action is ongoing or whether any arrests have been made. He merely needs to know that what he is doing is likely to have a tendency to obstruct, prevent, pervert or defeat the course of justice.”

We now turn to the practical implications of this provision on everyday events.

3. Would a tip-off about a Police Raid amount to Obstruction of Justice?

Earlier this month, as CNA reported, a club bouncer pleaded guilty to 6 charges of obstruction of justice for sending messages to chat groups about police raids.

Commenting on this case, Chooi reiterated that the tipster “need not know that a crime has been committed, nor that an enforcement action is ongoing or whether any arrests have been made. He merely needs to know that what he is doing is likely to have a tendency to obstruct, prevent, pervert or defeat the course of justice.”

In other words, even if the tipster did not send those messages with the intention or obstruct or pervert the course of justice, an offence may still be made out under the current iteration of Section 204A of the Penal Code.

Chooi added that the fact that the tip-off does not arise from insider knowledge and/or illegally obtained information does not matter.

In this case, the bouncer saw the raids himself and told others about it. Chooi stated that it was well-established that whether an offence under Section 204A is made out does not depend on how the offender comes across the information that he proceeds to tip-off others about.

All that is required is that the tipster be aware of facts that may amount to wrongdoing, and proceed to make the tip-off knowing it likely that the course of justice may be perverted.

We now turn to the practical implications of this provision on everyday events.

4. Would a tip-off about a Traffic Warden amount to Obstruction of Justice?

When asked about the common phenomenon where one who sees a traffic warden warns other drivers about it so that they may move their cars which are illegally parked, Chooi opined that even if this could theoratically constitute an offence due to the wide scope of Section 204A of the Penal Code today, there may be good reasons why such acts are not often prosecuted.

He noted that illegal parking is a commonplace and fairly trivial regulatory offence. From the standpoint of authorities, they are probably more concerned about reducing incidents of illegal parking than actual prosecution of illegal parking.

Seen this way, drivers who alert others about traffic wardens in the area (and thereby encourage them to move their cars away) may actually be promoting the goal of reducing incidents of illegal parking.

Chooi posits that Singaporean authorities do appear to subscribe to this notion especially where road traffic offences are concerned. For example, we have road signs on our expressways alerting drivers that a speed camera is up ahead, and road signs at certain junctions alerting drivers that there is a red light camera at that junction.

Put simply, we would rather prevent the offence than prosecute it. The philosophy, Chooi explains, is not so much to catch and prosecute offenders, but to prevent there being so many offenders in the first place.

For these reasons, there may be a practical and philosophical difference in how authorities view potential acts of obstructing justice for serious offences that are difficult to detect, and less serious regulatory offences.