Eugene Thuraisingam LLP X Founders Doc: What is defamation from the case of Rachel Wong v Olivia Wu?

In a video collaboration between Eugene Thuraisingam LLP and Founders Doc, our Suang Wijaya and corporate lawyer Rachel Wong came together to share their insights into defamation laws in Singapore and how they were applied to the notable defamation lawsuit of Wong Leng Si Rachel v Wu Su Han Olivia [2022] SGHC 15.

With the advent of social media, the evolving nature of communication and speech publication has presented a unique challenge to defamation laws. Defamation laws in Singapore provide legal recourse for individuals and companies alike if they believe they have been targeted by defamatory allegations shared online. But how exactly is defamation made out?

The video breaks down the 2022 defamation lawsuit of Rachel Wong v Olivia Wu to provide its viewers with key takeaways and points note from defamation laws in Singapore, with an emphasis on practising good social media hygiene.

You may watch the video below or head to the Founders Doc YouTube channel here to view other videos on related legal topics.

What happened in the Rachel Wong v Olivia Wu case?

The video provides a succinct explanation of defamation within the context of the exemplary case of Rachel Wong v Olivia Wu.

The Parties Involved

In this libel lawsuit, Rachel is the claimant and Olivia the defendant.

Dec 2019 | Rachel marries Anders

Apr 2020 | Rachel and Anders start proceedings to annul their marriage

Dec 2020 | Olivia, the friend of Anders’ current partner, takes to Instagram to post six stories alleging Rachel of being unfaithful during her marriage, with a man named Alan.

Apr 2022 | Rachel sues Olivia for defamation

Was defamation made out in the Rachel Wong v Olivia Wu case?

In the video, Suang explains that defamation constitutes three elements:

1. The statement must be published and be readable by a third party.

– Olivia posting the allegations online on her Instagram, which had been seen by her followers, can be regarded as publication

2. The statement must refer to the claimant directly or indirectly.

– The statements had made reference to Rachel, who had been a public figure

3. The statement lowers the claimant’s position in the eyes of the public.

– The statements involved allegations of adultery, which is behaviour widely frowned upon by right-thinking members of the public

On the face of the Rachel Wong v Olivia Wu case, all three elements are potentially made out.

The Justification Defence

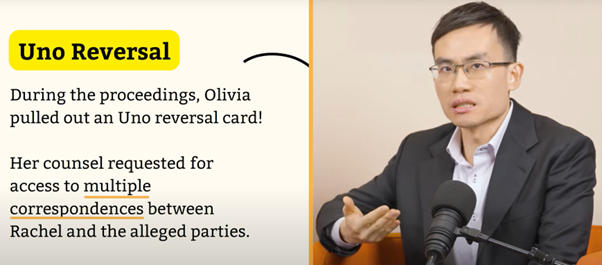

But with all the three elements of defamation seemingly made out, the case took a turn when Olivia raised the justification defence – that Rachel had committed adultery and that her statements about Rachel had been the truth and therefore cannot be deemed as defamatory.

In support of the justification defence (i.e. to prove that Rachel did have inappropriate liaisons with Alan), Olivia applied to Court to order Rachel to provide disclosure of Rachel’s diary entries and correspondence between her and the alleged parties.

The Judge had directed the orders to be made against Rachel.

However, before the Court made any findings of fact on the heart of the matter, the suit concluded with the parties entering an amicable resolution, the terms of which were kept confidential.

Olivia withdrew all her statements and made a public and unreserved apology to Rachel.

The Key Takeaways

The video wraps up by imparting upon the viewers three key takeaways:

- Think before you make a public statement

- If you make a public statement, make sure it’s correct

- Re-posting a defamatory post may amount to defamation

The Rachel Wong v Olivia Wu case underscores the importance of exercising caution and responsibility in one’s online interactions and presence – notably the need to ensure the accuracy of any public statements made to avoid liability. As Suang explains, under current law, publication could take the form of even private communication to a third-party over WhatsApp and would be sufficient to amount to defamation if the material is found inaccurate and harmful.

On an ending note, Suang and Rachel address the question of whether someone could face legal repercussions for the simple sharing of potentially defamatory content online even when they were not the original publishers of said content.

The short answer is yes – reposting, retweeting defamatory claims or statements are akin to its republication and could thus run the risk of violating defamation laws, even when one does not outrightly endorse it (for more information, see an article published on Today where Suang was invited to shed light on the topic).

While the video provides a useful overview of the expansive reach of defamation laws in the digital age, it should not be taken as legal advice. For tailored legal advice on defamation or civil matters in general, do contact us for any queries.